|

HUMANOIDS

- The subject of science fiction at the moment, but with more engineers and

artists getting involved, one day humans may have droids to sort out

everyday chores and as companions for the elderly and disabled. There are

thus serious social advantages to developing animatronic robots.

It

is though, a whole different ball game. You can start off with a steel

frame and hard actuators, but soon you will be into simulating body touch

and feel, including temperature, with appearance being perhaps the most

important aspect. If you are going to have a robot

about the house, it might as well look pleasing, like a beautiful painting

or car. We call this soft furnishings.

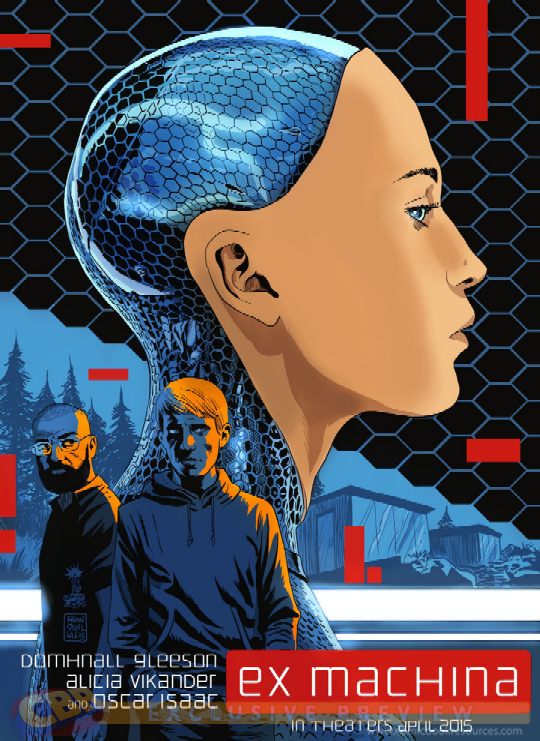

This

low budget movie pulls you in from the beginning and keeps you hanging

there until the startling revelation that the subject AI is more than

capable of outsmarting the humans testing it. The performance of Alicia

Vikander as the endearing robot with ambitions of her own, is nothing less

than brilliant.

Ex Machina (stylized as ex_machina) is a 2015 British science fiction psychological thriller film written and directed by Alex Garland in his directing debut. It stars Domhnall Gleeson, Alicia Vikander and Oscar Isaac. Ex Machina tells the story of programmer Caleb Smith (Gleeson) who is invited by his employer, the eccentric billionaire Nathan Bateman (Isaac), to administer the Turing test to an android with artificial intelligence (Vikander).

Made on a budget of $15 million, the film grossed over $38.2 million worldwide and received critical acclaim. The National Board of Review recognized it as one of the ten best independent films of the year. The film received

Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay and Best Visual Effects, while Vikander was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress and a

BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, and received several accolades for her performance.

If

BMS ever produce a female humanoid

robot, it would be a tough call between Alicia Vikander and Sean Young,

who played Rachael in Blade

Runner.

EX

MACHINA - Looks like the Welsh sci-fi film "The Machine,"

screened a couple of years ago at the Abertoir Film Festival. Both films focused on scientists who had created a female robot that ended up surpassing and challenging its creator. And both raised issues about what happens if a robot actually achieves a level of consciousness that makes us look upon it as human.

In the case of "The Machine," the robot was designed as a weapon and ended up with a higher moral sense than its maker. In "Ex

Machina," Ava is designed more as an exercise in ego on the part of Nathan. The films overlap in many ways but end up tackling slightly different aspects of their similar themes.

What makes "Ex Machina" compelling is how complex it is willing to go in the discussions about Ava's possible humanity. Caleb worries that Nathan has simply programmed her to flirt with him and to look like the type of woman he searches for on the Internet in order to cloud his judgment.

THE

GUARDIAN, 25 JANUARY 2015

At a key moment in novelist-turned-film-maker Alex Garland’s provocative sci-fi flick, a naive young computer programmer asks the Colonel Kurtz-like creator of an impressively human

artificial intelligence why he chose to sexualise his robot; to give it a gender, an attractive face, a flirtatious manner. The two-part answer is telling – first, that everything in nature is gendered, that all thoughts and actions are (on some level) driven by a reproductive urge, and no biogenetic impulse exists without a priori acknowledgment of attraction. For a machine to attain the status of “singularity” (the point at which the human and artificial become indistinguishable) it must have a sexual component. And second, hey, it’s fun – a primary pleasure that only the obtuse or uptight would wish to ignore or deny.

The same answer could be given to explain the form of Garland’s directorial debut, a dazzlingly good-looking technological thriller that occasionally dresses its weightier questions of the nature of intelligence – both artificial and natural – in the clothing of a somewhat salacious exploitation movie, replete with titillating displays of synthesised (female) skin and generically disavowed voyeurism. Yet at its heart is an ironic absence of sexuality, a detachment from desire similar to that exhibited in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, in which

Scarlett

Johansson’s predatory alien inhabits the form of an alluring young woman in order to prey, Species-style, upon unsuspecting humans. Just as

Blade Runner wondered whether its lifelike replicants could really fall in love, so Ex Machina spirals obsessively around the question not of artificial intelligence but artificial affection, worrying away at the authenticity of attraction as an indicator of consciousness itself.

SEXBOTS

- There is no point having a pretty face if you cannot communicate such as

to replace a male or female as a companion. Better still, if your robot

can also service other needs and make an omelet, there can be little

argument against such an appliance- one might even call it art. Some of

the latest dolls in platinum silicone are extremely realistic, many modeled

from real life. You can dress your robot in whatever takes your fancy,

with no nasty smells from not washing under the armpits.

We first meet Domhnall Gleeson’s wide-eyed, lonely IT waif Caleb from the wrong side of a computer terminal, receiving a message that tells him that he has won “first prize”. It looks like spam, but the workplace reaction announces that this is something more akin to finding the golden ticket in one of Willy Wonka’s chocolate bars. With admirable concision and clarity, Garland whisks Caleb to the vast estate of his CEO Nathan (Oscar Isaac), Norwegian landscapes providing a suitably anonymous “remote” backdrop for the boss’s imposingly modernist hideaway. Here, Caleb is to perform a “Turing test” (which crucially began life as a gender-identifying party-game) on Nathan’s latest creation; an elegant

robot named Ava with humanoid face and hands affixed to a cyborgy body structure that allows us (literally) to see right through the artifice of its humanity. When Caleb complains that the test will be flawed because he can see that his subject is a robot, Nathan (who shows signs of having “gone native” in the absence of human company) replies that the real test is whether Ava can pass for human despite the knowledge that she is anything but. In short, will Caleb fall for Ava in the same way that Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore fell for “Samantha”in Her, his ardour undiminished by the absolute awareness that she is an operating system. And will she respond in kind?

The idea may be an old one but its execution is fresh and vibrant enough to conjure an attractive illusion of originality. Key to the film’s success is a trio of impressively nuanced performances that keep us constantly guessing as to each character’s true motivations. As the perpetually drunken and bullish Nathan, Isaac is a mass of conspiratorial contradictions, his smile deliberately duplicitous, his self-mythologising manner carefully conniving, his dancing (to Get Down Saturday Night) genuinely alarming. At first glance, Gleeson’s Caleb seems Nathan’s polar opposite, an awkward geek out of his depth amid the sterile grandeur of his host’s home. Only when Ava enters the equation do Caleb’s true colours start to show, Alicia Vikander’s note-perfect depiction of ever-so-slightly unnatural movement (think of Yul Brynner’s walk in Westworld dialled down by about 99%) triggering unsettling responses. Blending balletic physical performance with Double Negative’s excellently rendered computer graphics, Vikander’s Ava beautifully blurs the line between “mecha” and “orga” (in the lexicon of

Spielberg’s AI), inflecting the most natural gestures – a tilt of the head, a roll of the wrist, a flicker of a smile – with a hint of artifice, subtly accentuated by a whispered symphony of gyroscopic noise.

As for Garland, we should not be surprised that he approaches his directorial debut with such confidence and wit. After all, he has tackled these themes before in the living/dead juxtapositions of his 28 Days Later screenplay, in the conscious/unconscious dichotomies of the novella The Coma, and (most significantly) in the playing-God inhumanities of Never Let Me Go, which he adapted for the screen from Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, and to which this alludes in a recurrent motif about “automatic” art (from robot reproductions to Jackson Pollock) and the search for evidence of a soul.

With its reflective surfaces, glacial soundscapes, and Kubrickian geometric compositions, this is knowingly seductive sci-fi cinema, its slyly subversive allegiances hidden by the two-way mirror of the silver screen, its androids dreaming of much more than mere electric

sheep.

THE

PLOT

Programmer Caleb wins a one-week visit to the secluded home of Nathan, the CEO of his software company. The only other person there is Nathan's housemate Kyoko, who Nathan says does not speak English. Nathan has built a humanoid robot named Ava with

artificial intelligence (AI) and wants Caleb to administer a Turing test, which tests an AI's ability to persuade the tester it is human. Caleb points out that this is not a fair test, as he already knows Ava is an AI; Nathan responds that Caleb must judge whether he can relate to Ava despite knowing she is artificial.

Ava has a robotic body but a human-looking face and is confined to her apartment. Caleb grows close to her, and she tells him she wants to go on a date with him. She reveals she can trigger power outages that temporarily shut down the surveillance system that Nathan uses to monitor their interactions. The power outages also trigger the building's security system, locking all the doors. During one outage, Ava says Nathan is a liar who cannot be trusted.

Caleb encourages Nathan to drink until he passes out, then steals his security card to access Nathan's room and

computer. After he alters some of Nathan's code, he discovers footage of Nathan mistreating earlier robot models, and discovers that Kyoko is also a

robot. Back in his room, Caleb cuts his arm open and investigates his flesh.

At their next meeting, Ava cuts the power. Caleb says he fears Nathan will reprogram her, "killing" her. Caleb tells her he will get Nathan drunk and reprogram the security system to lock Nathan in his room; that night, Ava will trigger a power failure, activating the security system, and Caleb and Ava will leave together.

Nathan reveals that he recorded their conversation with a battery-powered camera. He explains that because Ava seduced Caleb into helping her escape, she has passed the test. Ava cuts the power, and Caleb reveals that he already reprogrammed the doors to open.

Ava leaves her confinement and Nathan knocks Caleb unconscious. As Nathan begins to drag Ava back to her confinement, Kyoko stabs him with her kitchen knife. Nathan knocks her inert, but is stabbed to death by Ava. Ava acquires parts from another android, taking on the appearance of a complete human woman. Leaving Caleb trapped inside the facility, Ava is picked up by the helicopter meant for him and enters human society.

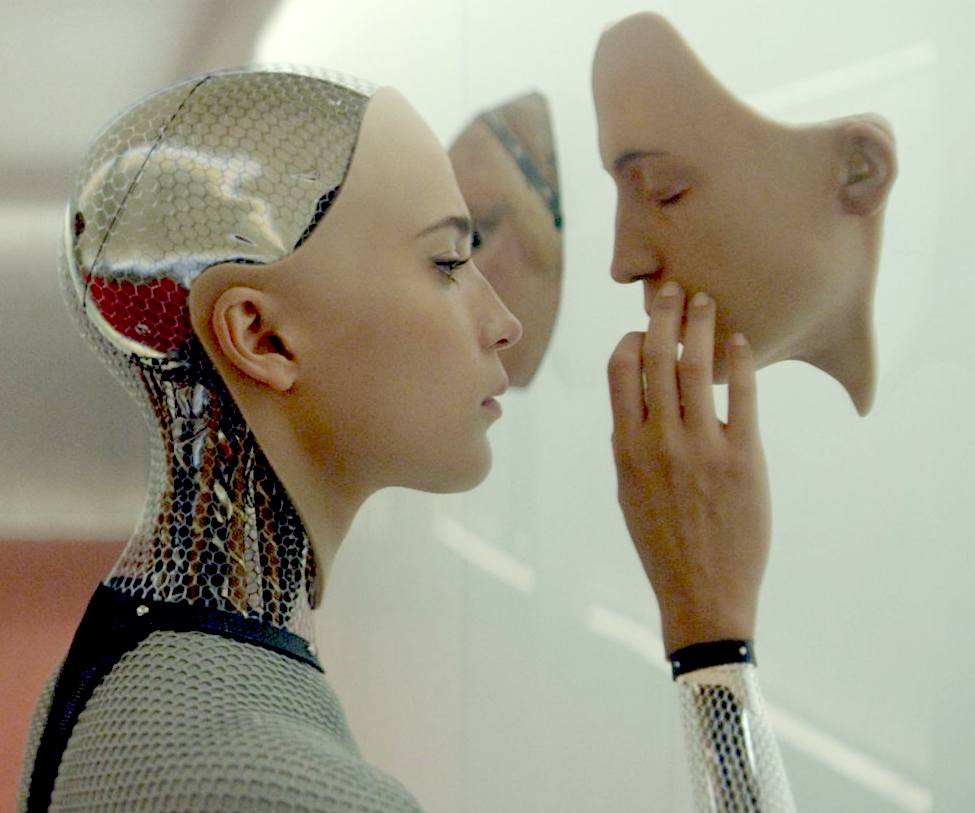

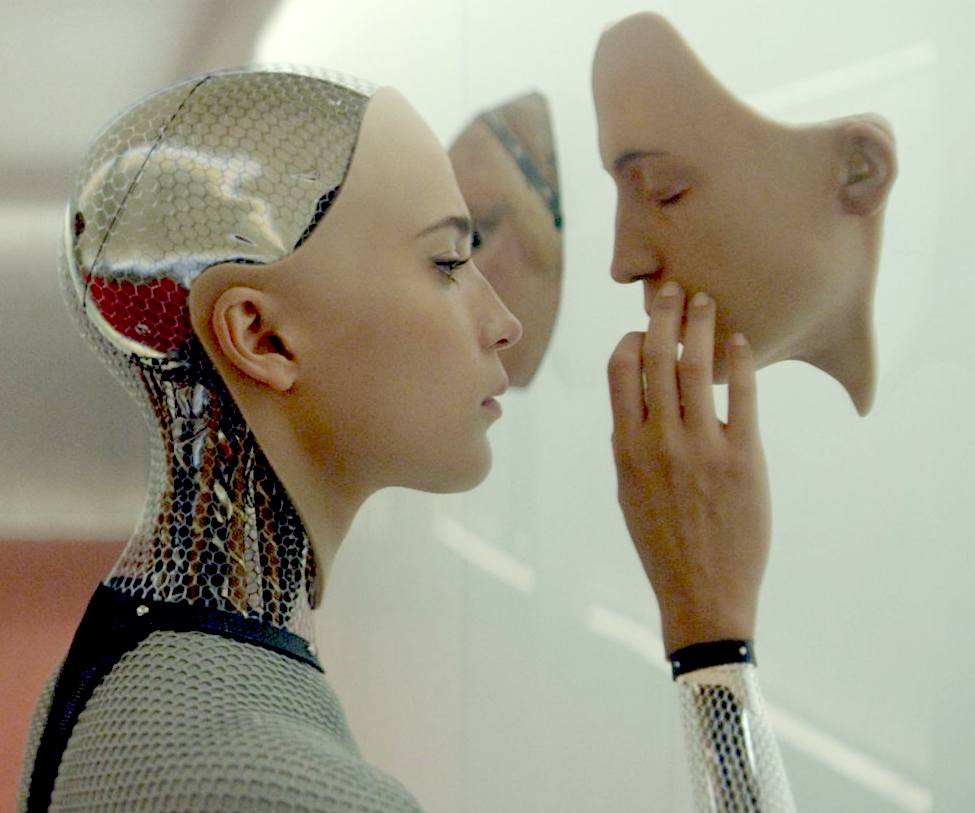

ANATOMY

LESSON - Nathan shows Caleb Ava's jelly-like computer brain.

THE

CRITICS

Ex Machina received critical acclaim for Garland's writing and direction, acting, atmosphere, special effects, and score. On website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 92%, based on 221 reviews, with a rating average of 8/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Ex Machina leans heavier on ideas than effects, but it's still a visually polished piece of work

- and an uncommonly engaging sci-fi feature." On Metacritic, the film has a score of 78 out of 100, based on 42 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews". The magazine New Scientist in a multi-page review said, "It is a rare thing to see a movie about science that takes no prisoners intellectually ... [it] is a stylish, spare and cerebral psycho-techno thriller, which gives a much needed shot in the arm for smart science fiction."

The New York Times critic Manohla Dargis gave the film a 'Critic's Pick', calling it "a smart, sleek movie about men and the machines they make". Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times recommended the film, stating: "Shrewdly imagined and persuasively made, 'Ex Machina' is a spooky piece of speculative fiction that's completely plausible, capable of both thinking big thoughts and providing pulp thrills." Steven Rea, Philadelphia Inquirer film critic, gave the film 4 out of 4 stars, writing: "Like stage actors who live and breathe their roles over the course of months, Isaac, Gleeson, and Vikander excel, and cast a spell."

Matt Zoller Seitz from RogerEbert.com praised the use of ideas, ideals, and exploring society's male and female roles, through the use of an artificial intelligence. He also stated that the tight scripting and scenes allowed the film to move towards a fully justified and predictable end. He gave a rating of 4 out of 4 stars, stating that this film would be a classic. IGN reviewer Chris Tilly gave the film a 9.0 out of 10 'Amazing' score, saying "Anchored by three dazzling central performances, it's a stunning directorial debut from Alex Garland that's essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in where technology is taking us."

Mike Scott, writing for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, said, "It's a theme Mary Shelley brought us in Frankenstein, which was first published in 1818. That was almost 200 years ago. And while Ex Machina replaces the stitches and neck bolts with gears and fiber-optics, it all feels an awful lot like the same story." Jaime Perales Contreras, writing for Letras Libres, compared Ex Machina as a gothic experience similar to a modern version of Frankenstein, saying "both the novel

Frankenstein and the movie Ex Machina share the history of a fallible god in a continuous battle against his creation." Steve Dalton from The Hollywood Reporter stated, "The story ends in a muddled rush, leaving many unanswered questions. Like a newly launched high-end smartphone, Ex Machina looks cool and sleek, but ultimately proves flimsy and underpowered. Still, for dystopian future-shock fans who can look beyond its basic design flaws, Garland’s feature debut functions just fine as superior pulp sci-fi."

THE

CAST

Domhnall Gleeson as Caleb Smith

Alicia Vikander as Ava

Oscar Isaac as Nathan Bateman

Sonoya Mizuno as Kyoko

Symara A. Templeman as Jasmine

Elina Alminas as Amber

Gana Bayarsaikhan as Jade

Tiffany Pisani as Katya

Claire Selby as Lily

Corey Johnson as Jay the helicopter pilot

FILMING

& PRODUCTION HISTORY

The foundation for Ex Machina was laid when Garland was 11 or 12 years old, after he had done some basic coding and experimentation on a computer his parents had bought him and which he sometimes felt had a mind of its own. His later ideas came from years of discussions he had been having with a friend with an expertise in neuroscience, who claimed machines could never become sentient. Trying to find an answer on his own he started reading books on the topic. During the pre-production of Dredd, while going through a book by Murray Shanahan about consciousness and embodiment, Garland had an "epiphany". The idea was written down and put aside till later. Shanahan, along with Adam Rutherford, became a consultant for the film, and the ISBN of his book is referred to as an easter egg in the film. Other inspirations came from films like Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, Altered States, and books written by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ray Kurzweil and others. Wanting total creative freedom, without having to add conventional action sequences, he made the film on as small a budget as possible.

The film was shot like ordinary live action. There were no special effects, greenscreen, or tracking markers used during filming. All effects were done in post-production. To create Ava's robotic features, they filmed the scenes both with and without actress Alicia Vikander's presence, which allowed them to capture the background behind her. The parts they wanted to keep, especially her hands and face, were then rotoscoped while the rest was digitally painted out and the background behind her restored. Camera- and body-tracking systems transferred Vikander's performance to the CGI robot's movements. In total, there were about 800 VFX shots, of which 350 or so were robot shots.

Filming

The film was shot over four weeks in 2013 at Pinewood Studios and two weeks at Juvet Landscape Hotel in Valldalen, Norway. It was filmed in digital at 4K resolution. 15,000 mini-tungsten pea bulb lights were installed into the sets to avoid the fluorescent light often used in science fiction

films.

The opening office scene is filmed at the Bloomberg Head Office in Finsbury Square, London.

DINOSAURS

- DOLPHINS

- HUMANOIDS

- SHARKS

- WHALES

|